I) Three Strikes

A) San Francisco Longshoremen’s Strike

1) Grievances

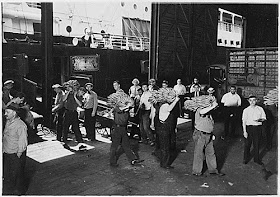

(a) The shape-up – longshoremen at this time were hired like day-laborers; they showed up at dock gates in a port, and the hiring boss chose those he was disposed to choose. If workers provided him with a reason to choose them (connections, bribes, kickbacks on the wages they were to receive that day), they were, of course, more likely to be chosen. The most important battle as far as the workers were concerned was to gain control of hiring practices (known as the hiring hall) so that they could control who would be sent to what job.

(b) Master agreement – workers demanded that all shipping firms agree to the same terms of contract, so that all workers on the west coast would be treated the same, and so that workers in other ports could not be used to whittle away the gains others might make.

2) International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) – the ILA was the nominal union on the west coast, although its influence was flagging during this time; its real source of power was its control of the ports on the east coast, and on the Gulf coast. The ILA was led by a man named Joe Ryan, one of the most spectacularly corrupt union officials in history; as the strike on the West Coast dragged on, he flew in and attempted to make a separate peace in each port, rather than the master agreement that was one of the demands of the workers; only the longshoremen of Seattle gave in to this ploy, however.

(a) Harry Bridges – the leader of the San Francisco local was named Harry Bridges. Originally from Australia, Bridges was a brilliant organizer. Although he was probably a member of the Communist Party, he unfailingly put the interests of his members first (although this did not stop efforts by the US government to try and deport Bridges for much of the next forty years as an undesirable alien).

3) Battle of Rincon Hill – on July 5, San Francisco police attempted to put an end to the city’s portion of the longshoremen’s strike by attacking pickets at Rincon Hill, killing two and injuring 109 others. This blatant favoritism by the police led to workers in the city to call for a general strike, which took place for the following two days. Workers took over many city functions during that time period—directing traffic, etc. The international office of the AFL, however, demanded that the San Francisco CLU end its support for the general strike, which they almost immediately did and the strike quickly ended.

4) Settlement –the longshoremen’s strike went on for another three weeks after this, however, ending on July 31, after 11 weeks, with an agreement to arbitration on the outstanding issues. Through vigorous job actions over the next year or so, however, longshore workers were able to gain most of their demands.

B) Minneapolis Teamster’s strike

1) Citizen’s Alliance – an alliance of business citizens, that is. This group of business leaders was determined to keep Minneapolis a bastion of the open shop.

2) Teamster’s Local 574 – led by a group of militant truck drivers who had been expelled by the Communist Party in 1928—namely the three Dunne Brothers (Vincent, Grant, and Miles) and Karl Skoglund—who were determined to organize truck drivers in the city.

(a) February 1934 Coal Driver’s Strike – the first blow to the Citizen’s Alliance leadership in the city was this strike; obviously, a great number of Minneapolis residents needed coal in the middle of February. The quick success of this strike made the organization of other truck drivers and warehouse workers much easier; by the middle of May the local boasted of over 5,000 members.

(b) May 1934 strike – called after employers refused to bargain with the union; many members of the Citizen’s Alliance were deputized. The Teamster local’s Woman’s Auxiliary was also involved in the strike; when this group was attacked by the police and five members were sent to the hospital, 35,000 building trades members declared a sympathy strike, with the city’s CLU supporting the decision. After several bloody battles, the employer’s group agreed to bargain with union.

(c) July 1934 strike – the union distrusted the employer’s association, and began almost immediately to prepare the membership for another strike, which came July 16. The crux of disagreement was jurisdiction over so-called “inside” workers (inside the warehouse, that is). Teamster’s Local 574 wanted to transcend craft unionism and move toward industrial unionism, which the employer’s association opposed—as did the union own international president, Dan Tobin.

(i) “Bloody Friday” – small group of “flying pickets” were ambushed by the Minneapolis police (as an investigation by Minnesota governor Floyd Olson proved), with the result that two of the pickets died. Some 40,000 workers marched in the funeral procession for their two stricken comrades.

(ii) Government arbitration – the arbitrators sent in by the government were distrusted by Local 574, and proved to be ineffective.

(d) Settlement – on August 22, the employers association agreed to union representation of inside workers, and all other union demands.

C) Toledo

1) February 1934 – strike effecting Spicer Manufacturing, Bingham Stamping, Logan Gear, and Electric Auto-Lite was called by Local 18384, a Federal Union, a sort of temporary union created by the Toledo Central Labor Union to begin organizing Toledo autoworkers.

(a) Little initial support at Auto-Lite – only 15 workers at the Auto-Lite plant joined the picket lines in February; only the solidarity of the workers at the other plants, and their refusal to go back to work without their fellow union members at the plant, got the Auto-Lite management to agree to take back the strikers and “bargain” with the union.

(b) Section 7a – (read the clause from page 15 of Korth book); “guaranteed” workers to choose a union, and to bargain collectively (the NIRA code gave manufacturers the right to set prices and production quotas amongst themselves, in return). Management attempted to meet this requirement by encouraging company unions; workers resisted this push, and attempted to establish unions under their control. In all three strikes, the main push for the workers was simply that management recognize the union as their bargaining agent.

2) Auto-Lite bargaining tactics – essentially, to stonewall the union in the hope that it would eventually fade away. Instead of bargaining in good faith, as the company had indicated that it would, they instead hired more workers, in order to expand the pool of trained strikebreakers, in the anticipation that another strike would follow in the immediate future.

(a) C.O. Miniger – owner and manager of the company since the company had moved to Toledo from Indiana to supply headlamps for Willys automobiles. Sat on the board of directors of the Commerce Guardian Bank; when this bank failed in 1933, he used an advanced warning to pull out the money of his company and his own personal accounts, while thousands of ordinary Toledoans lost their savings in the failure of the bank.

(b) Tear gas – the company also bought a large quantity of tear gas, in anticipation of trouble that would follow

3) Congress for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) – later known as the American Workers Party (AWP), which still later became the Workers Party. This group was led at this time by A.J. Muste, a (then) former Dutch Reformed Church minister; this organization was peopled with believers in Leon Trotsky’s “permanent revolution” (as contrary to Josef Stalin’s “revolution in one country”), left-wing socialists who believed that the economic distress of the country gave them a ripe opportunity to overthrow the capitalist system of the country (a belief which many capitalists shared).

(a) Lucas County Unemployed League – formed in late 1933 to begin organizing the unemployed in the county (mainly in the city of Toledo). They accomplished this by using such tactics as a “death march,” where a group of unemployed marched slowly around the county courthouse, pulling a wagon with a bell sounding the death knell; and by taking groups of unemployed into restaurants and insisting the owner send the bill to the Lucas County commissioners.

4) Second Auto-Lite Strike – concentrated upon the Auto-Lite and two affiliated plants; Bingham Stamping, and Logan Gear, both of which were partially owned by Miniger as well.

(a) April 13 – pickets set up after the membership of the local voted to strike the night before; approximately 400 workers from the plant walked the picket line, while about the same number of workers crossed the picket line initially. Picket line numbers were increased by the participation of other union members, and by the participation by members of the LCUL.

(b) Injunction – strikebreakers were being roughed up, verbally abused, and intimidated (followed, sometimes up the steps of their homes). On May 3, company lawyers asked for, and received from Circuit Court judge Roy R. Stuart, a sweeping injunction, limiting the number of pickets to twenty-five, and preventing the participation by anyone who had not been an employee of the Auto-Lite. The immediate result of this was that the number of strikebreakers who reported for work greatly increased, allowing the company to run full production, and essentially defeating the strike.

(c) Violation of the injunction – at the suggestion of Louis Budenz (later a member of the Communist Party, and later still a born-again Catholic and FBI informer), the members of the LCUL announced, in an open letter sent May 5 to Judge Stuart, that they were going to violate the injunction—which they began the next day. The members (rather small at this early time) were promptly arrested, and brought before Judge Stuart, where they were admonished not do that anymore, and released—whereupon they promptly left the courtroom and marched back to the plant to begin picketing once again. This action encouraged other members of the LCUL to join in. They would get arrested, raise hell at the courthouse, and be released, only to head back to the picket line. This “street theater” began to attract large crowds in front of the factory—and more importantly, began to diminish the number of strikebreakers to cross the picket line.

(d) Community uprising – by May 23, more than 10,000 people, men and women, were on the picket line surrounding the factory. Deputized plant security was on the roof with tear gas. A female picket was struck on the head with an object thrown from the upper floors of the factory; workers responded with a barrage of bricks that continued through the night. At midnight, the Ohio National Guard was mobilized; by the end of the six-day disturbance, this would be the largest peacetime mobilization in Guard history. The disturbance only ends when Ohio governor White promises not to use the Guard to re-open the factory; with the factory finally closed, Auto-Lite management agreed to negotiate with the union.

D) Southern Textile Workers strike – although valiantly fought by southern workers, the dispersed nature of textile workers communities meant that they received little help in their strike, which led to its failure.

E) Labor successes – the three successful strikes of 1934 succeeded because the workers conducting the strike were able to rely upon other workers in the community—something the textile workers in the South, because of their isolation, were not able to do. Although workers were certainly inspired by section 7a, and by FDR’s apparent positive response to labor, they did not rely upon the government to help them win their battles against employers – a lesson that the CIO did not learn.

II) Works Projects (Progress) Administration (WPA) 1935-1942

A) Productive jobs – WPA employees saw themselves as workers and citizens, not welfare cases; workers received nearly double to rate of pay of workers on earlier programs (although, at FDR’s insistence, still below the rate of the private sector, so that no one would be tempted to live on government largess), and they were exchanging their labor for money, just as they had during their employment in the private sector

B) 8,000,000 people put to work during the life of the life of the program

1) Toledo – Anthony Wayne Trail, Toledo Zoo

2) Cleveland – numerous bridges, Memorial Stadium

3) The Ohio State guide series

C) Popular Culture and the New Deal

1) Art

(a) Murals – numerous murals were painted in public buildings, inspired by Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco (local examples include the Perrysburg Post Office and various buildings at the Toledo Zoo).

2) Federal Writers Project

(a) State guides – government funded “guides” were produced for each of the 48 states; larger cities also got their own guides.

(b) Slave narratives

(c) Narratives of immigrants and cowboys, as well

3) Federal Music Project

(a) Created 34 symphony orchestras

(b) Sponsored numerous dance band

(c) Collection of folk music (Alan Lomax)

4) Federal Theater Project – perhaps the most controversial of the federal projects

(a) Living newspaper – writers and actors collaborating to produce drama out of recent news, and dramatizing current events.

(b) Ethnic theater groups – Yiddish, Spanish language.

5) Photography – not strictly WPA; photographers were also hired by the Department of Agriculture, and particularly the Farm Security Administration. The photographers often were able to publish their photographs in popular magazines of the day. When viewing these photographs today, one should keep in mind that these photographers were hired to take photographs by government agencies, in the expectation that these materials would help the government build its case for specific government programs.

6) Cultural forces outside of government

(a) Woody Guthrie

(b) John Steinbeck – Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men

(c) Warner Brothers Studio – the unofficial house studio of the New Deal; Jack Warner was FDR’s main supporter in Hollywood, outside of the acting and production talent.

7) Screen Actors Guild – although established earlier, the Screen Actors Guild becomes more of a force to be reckoned with during this time period (in fact, a second banana actor named Ronald Reagan begins a second career when he rises to the presidency of the organization in the 1950s).

III) Social Security Act (1935) – now synomomous with an old age pension, the program encompassed much more than this at its inception; it was an attempt to build a European-style welfare state, with cradle-to-grave coverage.

A) Help for the elderly

1) Immediate aid – a whopping $15 a month

2) Federal pension financed by payroll tax split evenly between workers and employers

B) Unemployment insurance – administered at the state level, which meant that compensation was higher in the north than in the south; the program was meant to counteract the insecurity caused working families caused by temporary layoffs.

C) Political, rather than fiscal, issue – because the program was supported by a tax paid by workers and employers (for whom the workers produced a profit), workers felt that they had “earned” benefits, which made it appear to them (and some of the more conservative elected officials who represented them).

D) Aid to Dependent Children – granted on a monthly basis, after a social worker visited the family to ascertain their needs.

E) Racial Inequalities – as the potential for more non-whites began to receive these benefits, the benefits became more controversial.

1) Racial code of the Social Security Act – the act excluded, at the insistence of Southern legislators, agricultural workers and domestic servants—or about 60% of the African American workforce.

2) Sharecroppers and farm laborers – excluded from benefiting from unemployment insurance, as well

3) Disparities in Aid to Dependent Children – families in Arkansas received approximately 1/8 of the total aid given to families in Massachusetts

F) Fair Labor Standards Act – ended ½ day on Saturdays as a usual workday, and made the 40-hour week standard nation wide; the FLSA also pegged the minimum wage to Southern wages of textile and lumber workers, in the hopes of eventually raising those rates.

G) Wagner Act – officially known as the National Labor Relations Act, but named for its Senate sponsor, Robert Wagner of New York.

1) Hoped to answer two problems

(a) Industrial unrest and social turmoil – as was seen in the labor actions in 1934

(b) Wage stagnation and under consumption – these two problems were seen by an increasing number of people in the New Deal as the reason for the Depressions grip on the economy of the country.

VI) Rise of the CIO – initially these letters stood for the Committee for Industrial Organization; after the break away from the AFL, the organization became known as the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

A) Formed in the fall of 1935 – by unionists inside the AFL who believed that unions had to begin organizing workers by industry to begin combating the economic clout of large corporations.

1) John L. Lewis – president of the UMW; to this point Lewis was an autocratic leader (and he remained that in the UMW). Lewis’ change of heart was probably dictated by his unions inability to organize “captive” mines—that is, the mines owned by the steel companies.

(a) Communist organizers – Lewis utilized numerous Communist and Socialist organizers in his drive, mainly because of their superior organizing results. When asked if he were concerned that these organizers might persuade workers to join these other organization, Lewis replied, “Who gets the pheasant, the dog or the hunter?”

B) Flint Sit-Down Strike (1936-1937) – in many ways, this strike was the defining moment for the early CIO, and certainly for the fledgling United Automobile Workers (UAW).

1) GM employed 80% of the Flint workforce at this time, either directly or indirectly, so the economic impact of the company on the community was huge, and the corporation could usually rely upon city government to be compliant with their wishes.

2) GM workers began strikes around the country in November and December of 1936.

(a) Toledo GM workers – had successfully struck the Chevrolet Transmission plant on Central Avenue in the spring of 1935, with hardly any violence; many Toledo union members had advocated asking other GM workers to go out on strike as well—in fact, a caravan drove to Flint. The AFL representative actively discouraged this action, however. The corporation responded by pulling out half the machinery in the plant over a Thanksgiving lay over, with a resultant loss in jobs.

(b) UAW plan – the leadership of the union planned to strike Fisher Body plants in Cleveland and Flint after the start of the year, when workers received a bonus from the corporation, and more labor-friendly administrations took office in Ohio and Michigan

3) The Sit-Down Strike – this tactic allowed a militant minority to shape events; by occupying the building, workers were able to ensure that their would be no scab replacements—and that the threat of attacks on the workers would be minimized because they were inside with all of the expensive machinery.

(a) First utilized in Akron – this tactic was first used by tire workers in Akron, even if Flint workers get most of the credit.

(b) Battle of Running Bulls (January 11, 1937)

(c) Workers seizure of Chevrolet Plant #2 forced GM to bargaining table.

IV) Presidential politics

A) 1936 Presidential election

1) Roosevelt Landslide – Roosevelt used a great deal of populist rhetoric in the election, calling the Republican Party “economic royalists” and “organized money.”

2) Roosevelt won 60% of the popular votes cast (greater than his victory over Hoover), and the electoral votes of every state except Maine and Vermont.

(a) African American vote – by 1936, African Americans voted overwhelmingly in favor of FDR over the Republican standard-bearer, in a reversal over long-standing tendencies to vote for the party of Lincoln. This occurs, despite some discriminatory practices in New Deal programs, for several reasons.

(i) “Black Cabinet” – second level bureaucrats and black leaders outside of the administration who provided advice to the administration; these African Americans were particularly influential upon Eleanor Roosevelt.

(ii) Eleanor Roosevelt – when African American singer Marion Anderson was refused the use of the DAR Hall in DC to hold a concert, Eleanor R. resigned her membership in the organization, and arranged for Ms. Anderson to give her concert on the Mall, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

B) Roosevelt Recession – FDR’s lack of ideology comes back to haunt him; because he was not a true believer in Keynesian economics (explain Keynesian economics), Roosevelt was never comfortable with the sizable deficit that his government was running; with his sizable victory in 1936, he decided to greatly reduce spending in 1937, with disastrous results.

1) Economic recession – the Roosevelt Recession probably contributed most to the disenchantment towards Roosevelt, and the gains by conservatives in the elections in 1938.

2) Political backlash

(a) Reaction to “packing” the Supreme Court – a reactionary court had ruled against Roosevelt policies in numerous cases to this point; FDR advocated being enabled to nominate an additional justice for each one over the age of seventy-five (which would have added four additional justices to the bench); both Republican and many Democrats claimed Roosevelt was attempting to become dictator. The public fallout here was probably less severe than the bad press this generated for the President.

3) Backlash against labor

(a) Monroe MI – Republic Steel private police force gassed SWOC headquarters and set fire to it.

(b) Youngstown – Gov. Davey, who labor had supported in the 1936 election, read the handwriting on the wall, and used the National Guard to protect and escort strikebreakers to another Republic Steel plant on strike in this city. Phil Murray, whom Lewis had appointed to head up the SWOC Little Steel organizing drive, called for FDR to assist in this crisis, which he refused to do; this was the beginning of the rift between Lewis and FDR.

(c) Chicago Memorial Day Massacre – Republic Steel employees in Chicago on strike were rallying when Chicago police opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing several; newsreel footage of this incident was withheld because officials feared it would be incendiary.

V) Conclusion