I. 1877—The Great Upheaval

A. Railroads—the “engine” of economic growth by the mid-19th century, but also caused a great deal of disruption in the neighborhoods that the trains passed through, particularly in this time before the grade the railroad tracks ran on was elevated.

1. Injuries to children—in these neighborhoods, children were regularly injured or killed because they were hit by a train.

2. Injuries to railroad workers—working on a railroad was very dangerous work, and workers were regularly maimed or killed, particularly working in the rail yard, coupling and uncoupling rail cars.

3. Watered stock—in this period of rapid expansion, railroad companies often sold more stock than they had assets or profits to cover; or the board of directors might issue themselves more stock to stave off (or profit from) a merger with another company. This was known as “watering” the stock, and was a huge problem for investors not on the board of directors.

4. Depression of 1873—caused in large part by the bankruptcy of Jay Cooke & Company, a Philadelphia investment bank financing the initial construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad. This depression lasted until 1879.

5. Cost-cutting—then, like today, companies were more concerned with the bottom line than with the well-being of their workers, and immediately began cutting wages and jobs—through thousands of people out of work

B. The Great Upheaval—the continuation of the depression meant that businesses continued to cut wages and workers, particularly in the railroad industry.

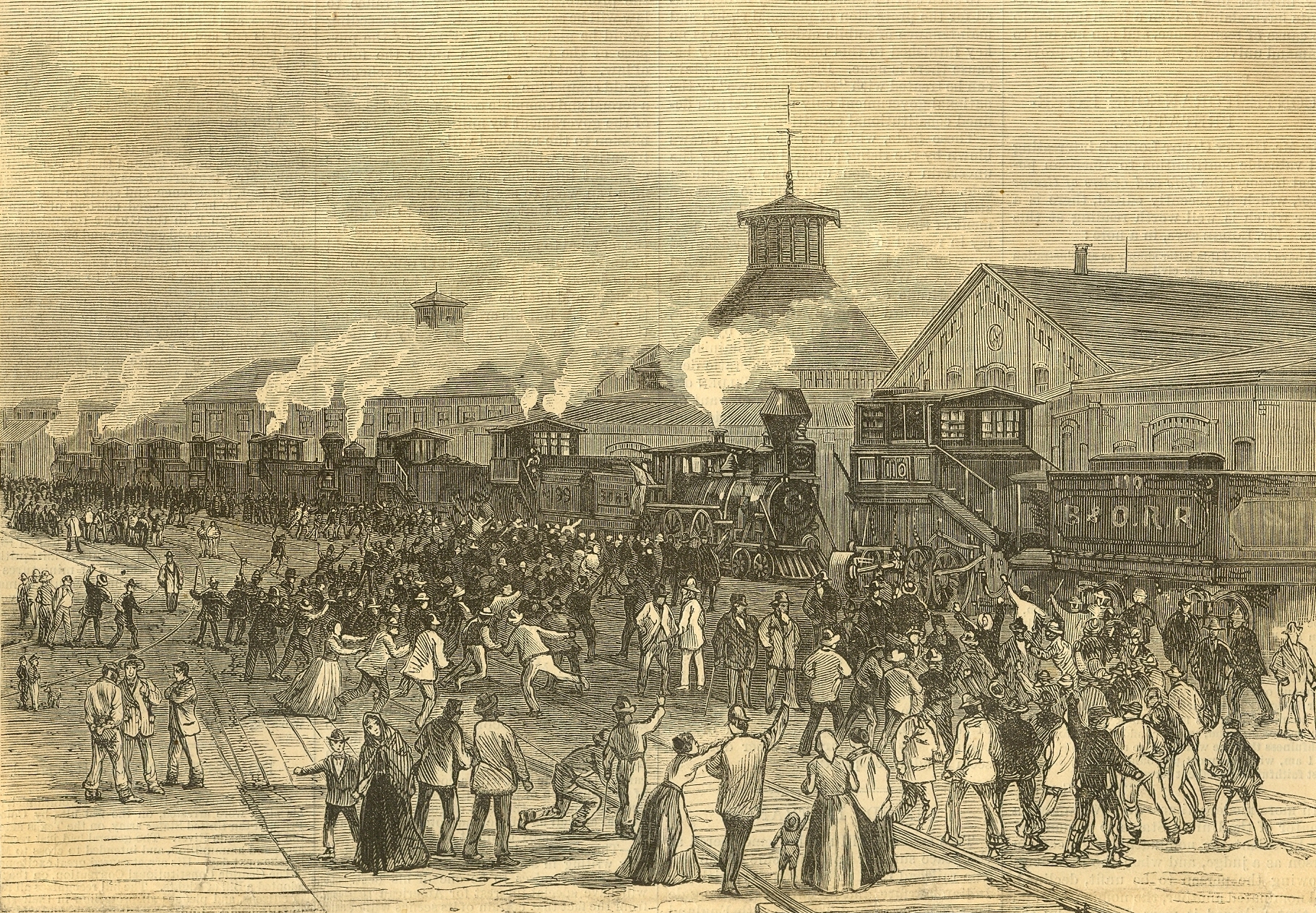

1. Martinsburg, WVa—a critical junction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Workers there decided to strike to attempt to force the company to rescind yet another wage cut in the summer of 1877. Workers prevented trains from passing through Martinsburg, despite the effort of the governor of West Virginia to mobilize the state militia. Workers also used their knowledge of and access to communication technology to workers around the rest of the country.

2. Pittsburgh—inspired by news of events in Martinsburg, and facing similar wage cuts, railroad workers in Pittsburgh went on strike against the Pennsylvania Railroad. When the militia was called up, they chose to bring troops from Philadelphia, were the Pennsylvania Railroad was headquartered. The arrival of this force of “outsiders” sparked a violent confrontation that eventually saw dozens killed, hundreds seriously injured, and much of the huge rail yard in Pittsburgh destroyed.

3. Toledo—In Toledo, agitation for an 8 hour workday for a minimum $1.50 a day wage led a number of workers, inspired by the job action of local railroad workers, to march from manufacturer to manufacturer to ask that the owner concede this demand—and to call for the workers to join the strike if the owner declined. That evening, a cache of arms stored since the abortive Fenian Uprising ten years before helped the local militia of business owners put down the rebellion.

4. St. Louis—inspired and aided by railroad workers, the workers of St. Louis actually engaged in a brief general strike, and workers for a time took over the governance of the city.

5. San Francisco—the Workingman’s Party in San Francisco was largely an instrument of anti-Chinese agitation, and the uprising there quickly degenerated into an anti-Chinese pogrom.

6. Chicago—inspired by the fiery rhetoric of Confederate veteran Albert Parsons and a number of German-American followers of direct-action anarchist Johann Most, workers in Chicago closed down railroad lines, and much else in the city, as well. Although there was not a general strike here as there was in St. Louis, workers sympathetic to the radicals in the Workingman’s Party (in Chicago, this meant the anarchist contingent) regularly struggled against employers in the city—as well as the police force that workers saw working for business interests in the city.

II. 1886 and Haymarket

A. Economic climate—by early 1878, the US economy began to recover from the depression, and there was a brief period of economic growth—and labor quiescence—before the next depression hit in 1883-1884.

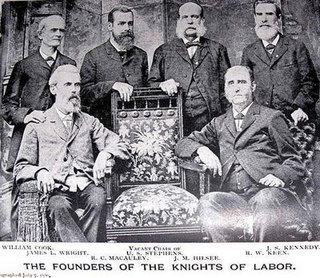

B. Knights of Labor (K of L)—founded by nine tailors in Philadelphia in 1869, in the organization’s early years of existence it functioned more as a fraternal organization than a labor union; it eventually emerged as the first general labor union in the United States, however, and attempted to organized all workers in the country without regard to gender or race (with one important exception).

1. Emergence—the K of L emerged in the late 1870s under the leadership of Grand Master Workman Terrence O. Powderly, a former railroad worker. The K of L organized workers into “local assemblies,” which could be based both organized by community location, or by craft.

2. Powderly’s claim—Powderly’s claim to abhor strikes was probably genuine, by the K of L was most successful in organizing workers by leading them into successful strikes.

3. 1885 Southwestern Railway strike—the most successful of the Knight’s strikes, which led to unorganized workers seeking out K of L organizers to join the union.

C. Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions (FOTLU) – a rival group to the K of L, consisting of skilled trades workers organized by craft. To set itself apart from the K of L, FOTLU began agitating for a standard 8-hour day in all trades and industries by May 1, 1886.

1. Strike at McCormick Reaper—in late April, workers went on strike for higher wages and a standard 8-hour day at the large factory in Chicago.

2. May Day—May 1, International Workers’ Day, FOTLU called for a one day general strike. A parade of several thousand marched up Michigan Avenue; after the festivities downtown, some workers ended up at the McCormick works to show support for the strikers there. When a sizable contingent of strike supporters showed up again the next day, the police were called out to maintain order; in a confrontation, the police fired on the crowd, killing several.

3. August Spies—in reaction, the editor of the leading German language newspaper called for workers to attend a protest rally at Haymarket Square the next evening—and he advised them to come armed.

4. Haymarket Riot—in dismal weather, a small crowd gathered on the evening of May 3, 1886 to listen to a serious of speeches. As the evening was winding down, a contingent of Chicago police arrived on the scene to ensure the crowd left quickly and peacefully—when someone from the fringe of the crowd through a bomb that landed in the midst of the police. The combination of the bomb blast and the ensuing gun battle caused seven police officers to be killed, and a number wounded. Reliable numbers for the crowd have never been compiled.

I) Homestead

A) Iron and Steel Industry – by the late 1880s and early 1890s, the iron and steel industry had overtaken railroads as the premier industry in the United States. Millions of tons of steel and steel products – rails, armor for railroad cars and locomotives, machines, machine tools (machines that made other machines), as well as for structural support for new high-rise buildings in the larger cities (which we know as skyscrapers).

1) Andrew Carnegie – former railroad executive secretary, Carnegie took the advice of his boss, Pennsylvania Railroad president Thomas A. Scott, and took the opportunity that presented itself to invest in the iron industry.

(a) Carnegie was already a wealth investor when he became involved in the iron and steel industry. Carnegie applied many of the techniques in business management that he learned in the railroad industry (particularly cost-accounting and business coordination, which helped keep his costs well below that of his competitors); he also retained control of the stock of his company, which allowed him to reinvest the profits back into the company, and therefore buy the latest equipment, and hire the best and brightest technical people.

(b) Vertical integration – Carnegie owned not only the steel mills that produced steel, but he also bought the mines that produced the iron ore and coal need for production, the coking plants that produced the needed coke (processed coal), and the railroad cars and shipping fleet needed to bring in the raw materials and distribute the finished product.

(c) Philanthropy – Carnegie used the wealth he helped create to greatly strengthen the public library system in the United States; he also endowed universities, built Carnegie Hall in NYC—and he advocated that other men of wealth follow his lead.

2) The drive to economize – the “secret” of Carnegie’s business success was that his management team was as driven to cut the costs of business as he was (in part because their reward system depended upon it—managers received a substantial portion of the savings they created for the company due to increased productivity; this same opportunity was denied workers who also contributed to this effort by working harder and longer).

(a) Productivity – defined as manufacturing, or making, more of an object at the same or less cost as compared with an earlier time period. Productivity is the basis for capitalist profit, which in theory allows them to “share” their decreased cost with the consumer, so “all” benefit.

(i) Business competition – Carnegie’s compatriots drive to decrease costs tended to drive out of the business those manufacturers who could not keep pace; because of the capital investment to get started in the business, however, a buyer (quite often Carnegie) could be found for the property. With more and more manufacturing capacity being held by fewer and fewer companies, the tendency of capitalist enterprises towards monopoly becomes more pronounced.

(ii) Business cycle – also known as the “boom and bust” cycle; businesses run like crazy to produce goods to sell, the market for a particular good becomes saturated, causing a glut, and then follows a time of little production, until demand picks up again.

(iii) Taylorism – Frederick Winslow Taylor was convinced that he could find the “one best way” to accomplish any job. Taylor himself came from an upper middle class background, but he became a machinist. “Soldiering” and what he perceived as inefficiencies of his fellow workers led him to develop time and motion studies, and to outline management practices devoted to prodding workers to put in 60-minute hours at work.

(b) Technology – this drive for greater levels of productivity also led American industrialists to use more machines than capitalists in other countries

(i) Lack of skilled workers? – Some historians and economists have argued in the past that because the United States allegedly lacked skilled workers, that industrialists relied more on the development of machines and machine tools to compensate. Today this reliance seems to have come about for other reasons

(ii) Labor costs – the increased level of machine use helped capitalists keep down the cost of labor, because the capitalist was able to replace skilled workers (who would have cost him more) with unskilled workers to tend the machines (who cost much less, and were easily replaced should they become recalcitrant.

(iii) This also undermined the position of the union worker, obviously, especially the skilled worker, who made up most of the ranks of the unions belonging to the AFL. Union members within the AFL umbrella fight battles to retain the benefits of the knowledge they had gained from working a particular job.

(i) “Featherbedding” – some AFL unions were successful for a time in keeping workers whose jobs had become technologically obsolete.

(c) Profits – by the early 1890s, the Carnegie Steel Company was making profits of more than $40,000,000 a year

3) Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers (AA) – in 1892, the AA was the largest and strongest union within the AFL, with approximately 24,000 members. The members of the union included only the skilled workers in iron, steel, and tin foundries; not considered for membership was a much larger contingent of unskilled workers, many of whom were new immigrants from Eastern Europe.

B) Homestead and the strike

1) City of Homestead – named after the nearby iron mill, Homestead was located several miles from Pittsburgh, up the Monongahela River. The town was completely dominated by the Carnegie mill—but the town leaders and townspeople identified with the workers more than Carnegie or his managers.

2) Homestead works – Ford C. Frick was hired by Carnegie to rid Homestead of the AA. After putting Frick in charge, Carnegie left for an extended stay in his castle in Scotland, but communicated in secret with Frick.

(a) “Negotiations” – Frick made demands upon the AA which he knew would be unacceptable, and then locked out union members when negotiations broke down in late June. Before the lockout, Frick had an eight-foot steel fence erected around the entire works

(b) Pinkertons – on July 6, a bargeful of 300 Pinkerton agents was discovered motoring up the Monongahela by union lookouts, who quickly notified union members in Homestead. Union members quickly occupied the Homestead works, and a fierce gun battle raged along the riverfront for most of the day, when finally the Pinkerton agents were forced to surrender; agents were forced to run a gauntlet in town, and many were severely injured as a result

(c) Won the battle, lost the war – the Allegheny sheriff was unable to recruit locals to “establish order,” and appealed to the governor for mobilization of the militia, and eight thousand troops arrived shortly to protect strikebreakers

(i) The Carnegie Company had the strike and union leaders arrested, some of who were charged with murder; after trials, all were found not guilty, but the defense efforts depleted the union treasury

III. 1894 Pullman Strike.

A. George Pullman – made his fortune hauling Chicago out of the muck; after the Great Fire of 1871, efforts were made to raise the remaining buildings as much of the swamp that the city was built on was filled. Pullman used this money to establish a company to build sleeping cars used on long trips by railroad companies.

B. Town of Pullman – as the company grew, Pullman became concerned about the effect the radicals in Chicago were having upon his workers, so several miles south of the city he built a town (housing, stores, public buildings, a hotel he named after his daughter Florence, even churches) which he rented to workers, but which he retained title.

1) “Model” town – Pullman the town was a great example of welfare capitalism—that is, subsidizing certain amenities for workers so they remain satisfied on the job.

2) Depression of 1893 – the economic depression of 1893 cut deeply into the profits of the Pullman Company, and Pullman responded by cutting wages and laying off workers, as any good capitalist would do.

(b) Pullman workers respond by going on strike in the spring of 1894.

C. Eugene V. Debs – a former officer of the Brotherhood of Railway Firemen, Debs in early 1894 became president of an early industrial union for railway workers, the American Railway Union.

1) Railway “Brotherhoods” – each specialty in the railroad industry had its own union, The Brotherhood of Railway Engineers, Brakemen, Conductors, Firemen; problems arose when railway companies settled with one of the brotherhoods, and they crossed the picket line while others were still on strike. The ARU is meant to be a solution to this problem.

2) 1894 ARU convention – was held in Chicago; a delegation of workers from Pullman, who plead for the assistance of the ARU. Despite Debs opposition, convention delegates vote to assist Pullman workers, and vote to boycott all trains with Pullman cars. Despite the fact that the ARU represents a relatively small number of workers, traffic all over the country is interrupted.

3) Government response – because there was little violence accompanying the strike the federal government was hamstrung; with a sympathetic John Peter Altgeld as Illinois governor, there was little chance that federal aid would be requested.

(a) Richard Olney – the AG for the federal government was a railroad attorney, and it was he who suggested attaching Pullman cars to mail trains (interfering with the mail is, of course, a federal offense).

(b) Troops from Fort Sheridan (and the Dakotas) are called in “to keep the peace,” which allowed the strike to be broken.

(c) Debs and other union leaders were arrested and held incommunicado, which also helped break the strike; Debs spent a year in jail in Woodstock, Illinois, which he spent reading socialist tracts; he becomes the Socialist Party candidate for president in 1900, 1904, 1908, and 1912, when he polled the largest number of votes to that time in history for a third party candidate.

No comments:

Post a Comment