I) The Beginning of the Modern Civil Rights Movement

A) New Deal – from 1935-1936, African Americans were an important part of the “New Deal Coalition,” which demanded, like other members of that coalition (white ethnics, labor, etc.) made demands upon the government which they expected would be met.

B) 1943 March on Washington – although this march never really took place, the fact that the President (FDR) reacted by creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) was a victory for African American activists.

C) NAACP – from the outset of the New Deal, the NAACP had been pursuing a number of lawsuits in order to overturn the practice of “separate but equal” that had been institutionalized since Plessy v. Ferguson.

1) Brown v. Board of Education – in 1954, the Supreme Court handed down a decision in a case in which an African American parent had sued the Topeka (KS) board of education over the maintenance of separate schools for white and black students. The Court agreed with plaintiff Brown that separate school systems were inherently unequal, and directed that the practice be ended with “all deliberate speed.”

2) Federal Government’s Amicus Brief—the Truman administration filed a number of amicus briefs supporting challenges to segregation that argued that the foreign policy interests of the United States were threatened by the continuation of segregation.

II) Southern White Reaction – Brown v. Board of Education has long been held as the beginning of the of the modern civil rights movement; but what the decision really signaled was the recognition on a part of some whites in government that African Americans should be accorded full rights as citizens, largely to further the aims of the Cold War. Not all whites were willing to recognize this fact, however, inside or outside of government.

A) Massive Resistance – the vow on the part of most southern white politicians to resist any and all efforts on the part of the federal government to integrate southern institutions.

1) Little Rock Arkansas – one of the earliest integration efforts was at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. Central High School was, to this point, attended largely by white working-class students (the integration of working-class schools is a practice that would be repeated around the country—including places like Boston). The governor of Arkansas, Orville Faubus, promised to resist the federal government order to integrate Little Rock schools. A huge crowd of whites turned out to jeer and threaten and throw rocks at the ten African American students who attempted to enter the school the first day. Reluctantly, President Eisenhower called out the 101st Airborne Division to ensure that students in Little Rock could attend school.

2) University of Mississippi – rioting broke out, with whites going on a rampage that again had to be quelled by the 101st Airborne (including members of the fraternity of which Republican US Senate leader Trent Lott was president of—where twenty-seven weapons were confiscated), when James Meredith attempted to enroll at the University.

3) University of Alabama – George C. Wallace proclaimed that he would stand in the school house door to prevent any African American students from enrolling at the university—which he did, although he quickly stepped aside once his point had been made.

III) African American Action – the white reaction of massive resistance did not come mainly from government action, but from the pressure that African Americans, mainly young people (college and high school students), placed on the government to live up to the promise of equal opportunity. Martin Luther King became the focal point of the modern civil rights movement, but it was the actions of numerous African Americans--and some whites--the forced a change.

A) Montgomery bus boycott (1955)

1) Rosa Parks – Mrs. Parks was much more than the popularly portrayed old woman who was tired from a day at work; she was secretary of the local NAACP chapter, and had had regular run-ins with the Montgomery Bus Company over her treatment on the buses.

2) E.D. Nixon – Nixon was an official in the local chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and the president of the NAACP chapter; at the beginning of the boycott, he sought out all the local black ministers to lead the boycott, feeling that this would make it seem less radical to other blacks; he first asked the new minister at the Third Baptist Church, Martin Luther King, who declined; after all other ministers also declined, Nixon was able to persuade King to assume the responsibility.

(a) Nixon and others coordinated the car pool service, which replaced the bus service in the black community; many of the drivers were college students who stayed home to provide the service

3) Martin Luther King, Jr. – feared about maintaining his new pastorate, with this high-profile task, and about the safety of his family (rightly, as it turned out, since shortly after his assuming leadership of the boycott his home was firebombed)

(a) After nearly a year, the Montgomery Bus Company capitulated, and agreed to remove the boards that segregated the riders.

B) Result of the success of the boycott guided King into a new role

1) Greensboro, NC – Greensboro was a city that prided itself on its progressive race relations; when 4 North Carolina A & T freshmen—Ezell Blair, Jr., David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Franklin McCain—decided to sit at the Woolworth’s lunch counter on February 1, 1960. The next day, these four were joined by twenty more; and eventually hundreds more (including a contingent of white female students from the nearby North Carolina Women’s College)

(a) Inspired black students throughout the south to similar actions.

2) Nashville, TN – led by students from the American Baptist Theological Seminary and Fisk University like John Lewis, Marion Berry, and Diane Nash, who were in turn led by a northern born black minister named James Lawson, who was committed to using Gahndian non-violent methods to foster social change.

3) Atlanta University – the “Black Ivy League;” led by Lonnie King and Julian Bond, who attempted to integrate public facilities in Atlanta; group was quickly arrested and they spent most of the day in jail—but this action turned middle-class blacks into freedom fighters.

D) Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) – at a meeting on April 16, 1960 in Raleigh, NC SNCC was formed; decided to remain independent from other civil rights organizations like NAACP, CORE, and SCLC.

1) Nonviolent confrontations – attempt to integrate interstate bus transportation

(a) Birmingham, AL –1st bus was allowed to leave but the KKK firebombed the bus on the highway, and the passengers were beaten as they tried to escape the inferno, until the US Marshall accompanying them drew his pistol and fired it into the air; 2nd bus of riders was set upon the group of whites at the bus station in Birmingham, and were allowed to beat passengers for five minutes before police showed up (by pre-arrangement).

(b) Mississippi – less violence then in Alabama, but the passengers were arrested and charged with “inflammatory riding,” saddled with high bails and eventually with unreasonably long jail terms (some even served time at Parchman Farm)

F) Albany (GA) Movement (1962) – an attempt by local African Americans to integrate public facilities, and to open bi-racial talks; the movement was led by SNCC until a local group called in King, which led to a sometimes bitter internal struggle. Albany police chief Laurie Pritchett restrained his officers from publicly abusing the protesters; the lack of conflict led to an overwhelming defeat.

G) Birmingham – after the lesson of Albany, King realized that he for nonviolent tactics to be successful, he needed a foil that would be more physically active than Pritchett.

1) Television – the violence of the Birmingham police, and their attack dogs and high-pressure hoses, repulsed much of the nation—and won a great deal of sympathy for the civil rights movement

2) Youth join the Movement – as more adults were arrested in Birmingham during the protests, King okayed the use of teenagers (and younger children) who faced Bull Connors’ police and dogs and fire hoses, which increased the impact for viewers on television.

3) “Letter from Birmingham jail” – King’s most famous writing distilled the aims of civil rights movement.

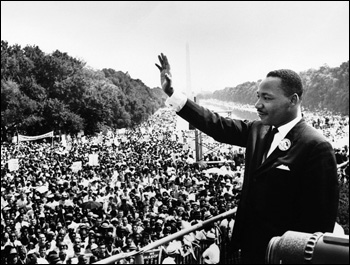

H) March on Washington – King’s “I have a Dream” speech, which was predated by a much angrier speech by SNCC leader John Lewis (which was less angry then it was originally intended, because the UAW’s Walter Reuther threatened to pull the union’s funding from the March).

I) Civil Rights Act (1964) – LBJ’s greatest moment, despite the rift it caused with former Senate colleagues.

J) Freedom Summer (1964) – the program created by SNCC to register black Mississippians to vote; recruited black and white college students, who were trained in nonviolent tactics at Miami University in Oxford in the spring of 1964.

1) White volunteers – SNCC first recruited a large number of white volunteers in 1963, in an early voter registration drive.

2) 1964 – more whites joined the effort; the hope of SNCC leaders was that by having prominent whites involved (including the son of California governor Pat Brown—Jerry Brown) there would be less danger for all involved

3) “Mississippi Burning” – three SNCC volunteers—one black and two whites—were kidnapped and murdered by the KKK

(a) Inordinate attention paid to the deaths of the white volunteers, which caused resentment among SNCC members; from this point white members are asked to leave the organization, and the black pride attitude becomes more prevalent.

K) Voting Rights Act (1965)

1) Selma – home to another reactionary racist, Sheriff Jim Clark; the police chief Wilson Baker maintained peace in the city early on—which hindered the voting rights campaign greatly.

(a) Decided to begin marching registrants to the Dallas County Courthouse, which Clark found provoking; Clark responded by ordering his deputies to beat protestors, despite the presence of television cameras

(b) “Bloody Sunday” – March 7, 1965; Hosea Williams and John Lewis led marchers, who were met at the Pettis bridge by the combined force of the Dallas County deputies an the Alabama State Troopers, who descended upon the marchers with a rebel yell and club all marchers they could reach senseless; ABC interrupted the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg” (the trial of another group of racists) to broadcast footage of the carnage.

(c) Presidential address – LBJ addressed a joint session of Congress calling for the passage of the Voting rights act, and quoted the famous song of the Movement “We Shall Overcome.”

(d) March 21—march to Montgomery resumes; Wallace was called to Washington and given the “Johnson treatment.”

(e) Bill signed into law August 6, 1965.

1) Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike—1,300 municipal workers in Memphis walked off their jobs in protest of years of ill-treatment. Just a week before, 2 sanitation workers were crushed to death in a malfunctioning garbage truck. Many sanitation workers, in fact, still qualified for welfare after working a 40-hour week. African Americans were relegated to the dirtiest, lowest-paying jobs, with not chance for advancement. In addition, African American workers were regularly verbally abused by white supervisors, including grown men being referred to as "boy."

2) Assassination of MLK--King had earlier visited Memphis, at the beginning of the strike, and promised to return to assist the workers in their struggle. King returned to the city on April 3, and a huge rally was held that evening at a local African American church. The next evening, as King was waiting to go to dinner on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, he was shot and killed by an assassin hidden in a building across the street. Mayor Henry Loeb still refused to negotiate with the sanitation workers, however, and President Lyndon B. Johnson sent his own negotiator to settle the dispute. An agreement was finally reached on April 18 that ended the strike; the union had to threaten another strike that summer, however, to get the city to live up to that agreement.

IV) Conclusion

No comments:

Post a Comment